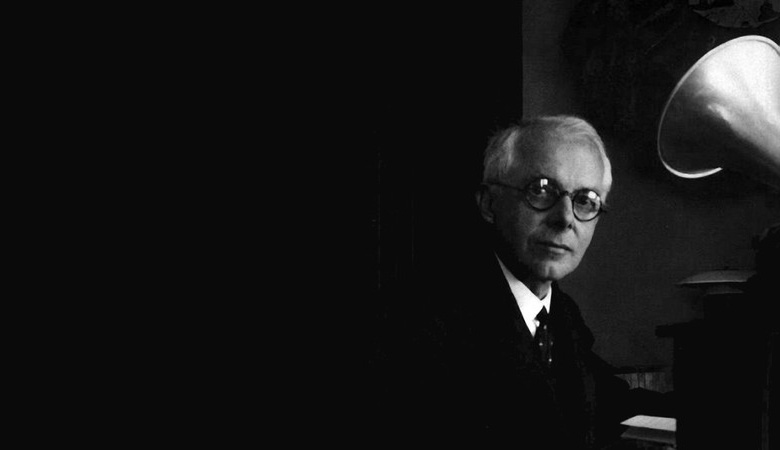

Béla Bartók

String quartets

31 March 2023

by: Bas van Putten

The String Quartet Biennale celebrates in grand style with Béla Bartók. All six of his string quartets will be performed on Sunday afternoon 28 January by three world-renowned quartets: the Belcea Quartet, the Doric String Quartet and the Jerusalem Quartet. Bas van Putten, also a speaker on that afternoon, sheds light on Bartók’s extraordinary oeuvre.

Schizophrenic combination of extremes

Have you ever heard Bartók’s First String Quartet (1909)? The Wagnerian echoes of Tristan und Isolde are unmistakable in the intense melancholy of the first movement. It’s something you wouldn’t expect from that always serious-looking Hungarian, who is known for his analytical mind. It was that mind that gave birth to the excitingly icy Allegro barbaro for piano, just two years after his first string quartet. The second movement of this string quartet, however, foreshadows that side of him. The allegretto has strange, repetitive, almost machine-like movements. In the finale, the atmosphere is reminiscent of Eastern European folk music, the music that folk music researcher Bartók collected on his expeditions from Hungary to Romania, from North Africa to Turkey, and which would profoundly and lastingly influence him as a composer.

Béla Bartók

The seemingly schizophrenic combination of extremes, from jarringly dissonant to crushingly beautiful, is found in all six of Bartók’s string quartets. But this is not the expressiveness of a man who, à la Wagner, reveals their inner world for all to see. A Bartók does not shout his pathos from the rooftops, although in 1902 the symphonic grandeur of Richard Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra made a huge impression on him. And in the same way, he was captivated by Liszt’s virtuosity. A constant factor in Bartók’s music, despite all of its dancing merriment and barbaric vitality, is a sense of isolation and distance, a loneliness that wants to be alone with itself. On the other hand, the music expresses with insane directness the speed of thought, the liveliness of the great mind that Bartók was. It is his virtuosic ingenuity that draws you into this strange, sometimes inhospitable world, this frenzy of manic escalating imagination and energy. In the allegretto pizzicato of the Fourth String Quartet, an absurdist giant guitar strums, and what comes next sounds like Jimi Hendrix’ spirit possessing a group of Hungarian folk musicians. The finale may well be the first piece of rock music in the history of classical music.

Doric String Quartet (photo Ben Bonouvrier)

Kinship with Beethoven

Much comes to mind, but above all the music of the one man the great pianist Bartók – for great is what he was – admired and had played since his childhood: Ludwig van Beethoven. They resemble each other in both their unbridled energy and the immeasurable internalization of their slow movements, their intellectualistic precision. Just like the 19th-century conductor and pianist Hans von Bülow characterised Bach’s Das wohltemperierte Klavier and Beethoven’s piano sonatas as the old and new testament of keyboard literature, Beethoven’s sixteen string quartets and Bartók’s six could be called the old and new testament in their genre. In their ambition, they are equal to each other, in their intensity, they are related.

What prompted Bartók to write six string quartets, a genre that was on the wane in the nineteenth century? Ambition, no doubt. But even more so, his connection with the past. With the Western music history from Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms to Schoenberg and especially Stravinsky, who out of all his radical contemporaries impresses him the most and whose influence is evident after 1920; in the allegro of the Fourth String Quartet (1928), the four strings explode with the mechanical outbursts of Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps. With the not only indigenous folk music, which he archives as a scientist and places in its historical contexts. But above all with the Central European musical tradition of Beethoven’s sonatas and quartets.

While the outside world considers Bartók to be a modern composer along with Schoenberg and Stravinsky, he sees himself as a traditionalist, someone who continues the great work of great predecessors at the highest level that he can achieve. While being in close contact with the present. Meeting Debussy in 1907 was a shock. He performs Schoenberg’s atonal pieces for solo piano Op. 11 in 1909, before they were published. His discovery of Stravinsky’s Sacre in 1917 is a turning point. On the other hand, he writes in 1923, while everyone sees him as an avant-garde composer at that time, that his music is completely tonal, has nothing in common with the ‘objective, impersonal’ musical language of those years, and is therefore the opposite of modern.

Jerusalem Quartet (foto Felix Broede)

Folk melodies

Bartók may also have been trying to say that the roots of his radical change of style in the 1920s lie in folk music, but he didn’t want his critics to pigeonhole him as a folk music composer. The folk music, with its unusual scales, helps him to break free from the traditional Western major-minor harmony, feeds him with the rhythmic and melodic richness that unfolds with scorching intensity in the quartets. Bartók did not use literal folk melodies in his quartets, as he believed that cultural appropriation was wrong. However, the spirit of folk music is everywhere in his music. In the ornamentation, in the strong (dance-like) rhythms and melodies, in the glissandi and the unusual metres, in the pagan roughness of the performance.

With his unusual tools, Bartók accomplishes the classical task of the string quartet composer; to achieve a sublime synthesis of high-quality technique and psychological depth. Everything that fascinated him is poured into it, all conceivable techniques from Western music history, all raw folk art that the musical elite overlooked.

Belcea Quartet (foto Marco Borggreve)

Expression, first and foremost

Bartók’s music is technically and structurally sophisticated. There is a lot to say about it from a musical analysis perspective. Such as about polymodal chromaticism, a technique that uses all twelve tones of the Western tonal system, sometimes bordering on Schönberg’s twelve-tone system. About the symmetrical forms of the Fourth and Fifth Quartets. About bitonality, the simultaneous use of two or more tonalities. About fugues and counterpoint, eerie night music, and new playing techniques, from the glissandi and tremolo figures to Bartók-pizzicati that snap like whip lashes.

For Bartók, however, all those technical aspects must, much like in the classical tradition, always bend the knee to emotional expression. He sees himself as a deeply traditional artist of expression. In 1909, he writes that he cannot see music in any other way than as an expression of unlimited enthusiasm, despair, sadness, wrath, revenge, consuming hope, and sarcasm. In that expressive diversity, the artist reveals himself according to Bartók, but much more fully than in the nineteenth century, when composers mainly expressed their elevated feelings. In his own time, he says, composers can express anything, including the dangerous and dismal, repulsive and malevolent emotions that used to be taboo. In the passionate and sometimes ruthless but mysteriously unexhibitionist ferocity with which Bartók explored and stretched those means of expression, he is in his own way at least as pioneering as Schönberg was for the grammar of the 20th century.